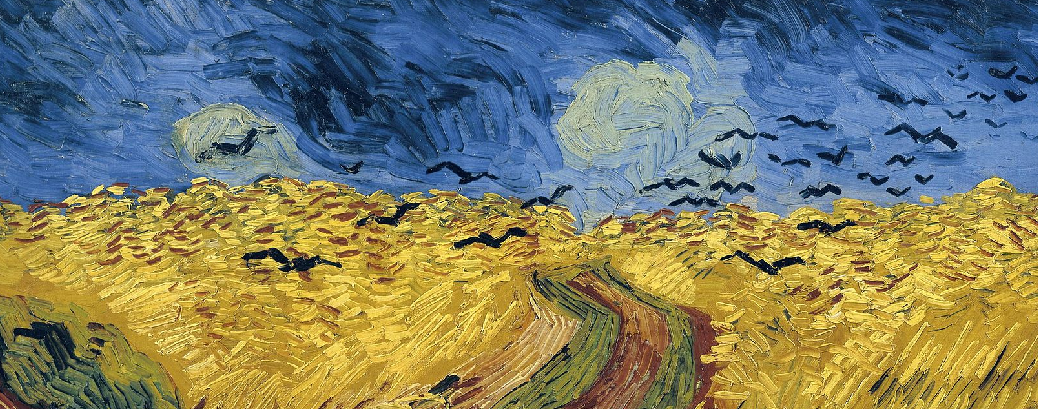

The picture above is by Vincent Van Gogh (obviously says you), it lives in the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam and is called ‘Wheatfield with Crows’. It was painted in 1890 – possibly his last picture. Vincent didn’t know about climate change or intensive agriculture; if he had, he would probably have cut the other ear off and left the crows out. Continue reading Ireland Pollinator Plan 2015-2020

Tag Archives: Wildlife

Pollination and Honey Bees

So, why are honey bees such important pollinators?

From an ecological point of view there are at least 3 reasons:

- Honeybees have evolved in tandem with certain flowers and they have adapted to facilitate each other;

- One bee is able to rapidly communicate the location of a pollen/nectar source to the whole hive and an army sets out;

- The bees then concentrate faithfully on that flower species until the pollen runs out or the nectar dries up, at which point the job of pollination is accomplished.

These features obviously make the honey bee important from an agricultural/commercial point of view. In addition, hives of bees are mobile and can be moved from crop to crop – an arrangement which can suit bees, farmers and beekeepers so long as everyone has a bit of respect. Wouldn’t that be great?

But some detail: Continue reading Pollination and Honey Bees

Ancistrocerus nigrocornis?

Look at this glamorous, bespangled wasp and tell me – is this Ancistrocerus nigrocornis?

Click here for more about Irish wasps

Copyright © Beespoke.info, 2016. All Rights Reserved.

Bee Trees – Ivy (Hedera helix)

Beekeepers know Ivy is a great plant for the bees but is it a tree?

It is when it’s got a great thick woody stem and a big bushy crown with flowers all over it. Continue reading Bee Trees – Ivy (Hedera helix)

Heather Ecosystem

When beekeepers think heather, they think weather and ‘Will it ever stop bloody raining?’

Or you might wonder – ‘IS there a flow at all?’ Because often there isn’t and you can never tell in advance if it will or if it won’t. Heather honey is the most bewitching and frustrating of all honeys; if you can get a crop of sections or cut comb honey it’s close to heaven and so costly and disappointing when it fails.

But there’s more to it than the weather. It’s the ecology – Stupid! Continue reading Heather Ecosystem

First Swallow?

1st April 2016 – Maganey, Co.Kildare

14th April 2015 – Dunlavin, Co.Wicklow

22nd March 2014 – Maganey, Co.Kildare

Blooming Gorse

The gorse is in bloom early this year, although what is it they say – ‘When gorse is out of bloom, kissing is out of fashion’ – is that it?

Look out for orange/brown pollen loads – along with the brighter orange from the snowdrops.

In fact, when the weather does warm up and the bees are active and bringing in that brown pollen it is worth going out to watch them working the gorse because the flower is specially designed to make best use of the bees for pollination. Enjoy the strong coconut scent of the flowers while you’re at it. Continue reading Blooming Gorse

In Praise of Ravens

When I stepped out the front door this morning – a raven flew over and let out 3 loud caws which echoed round the yard and here was me thinking I was all alone up here with the snipe and the hares. Being curious birds he didn’t go far but turned and came back for another look and was quickly joined by second raven. I could see from the tilt of their beaks that they were looking down on me – then they were gone – sailing across the sky without a care in the world.

My first close encounter with a raven with was in Shetland. I was on my hands and knees doing a vegetation survey on a heathery bog when I heard the distinct sound of a pebble drop into puddle – ‘plop’. I looked all round me but could see neither pebble nor puddle. Then I heard another plop but realised the origin of the splash was above me! When I looked up – there was a raven hanging in the sky directly overhead and looking down his beak at me. He flew away but kept coming back so see how I was getting on. I was charmed, it was lovely to have some company in such a remote place.

I still like to watch ravens they seem to be very happy birds, they get together in the sky and indulge in all sorts of aerobatics like flying really close together on synchronised wings or they’ll tuck their wings right in and flip over in the air, even flying upside down for a beat at times. Another thing they seem to enjoy is locking claws and falling through the sky together – first to let go is a chicken. And such a range of calls they have – such vocal dexterity.

On a slightly different species but same family, we came across a tame jackdaw one day by the river. He had a white ring on his leg and kept trying to land on our shoulders but settled instead on the hedge. One of the dogs, a terrier who shall remain nameless took to yapping at the bird as he sat in the hedge. Instead of being alarmed and flying off – the jackdaw took to barking back at him.

Charles Dickens loved ravens, in fact he had two as pets. Here’s what he tells us about them in the Preface to Barnaby Rudge:

“He slept in a stable – generally on horseback – and so terrified a Newfoundland dog by his preternatural sagacity, that he has been known, by the mere superiority of his genius to walk off unmolested with the dog’s dinner from before his face. He was rapidly rising in acquirements and virtues, when, in an evil hour, his stable was newly painted. He observed the workmen closely, saw that they were careful of the paint, and immediately burned to possess it. On their going to dinner, he ate up all they had left behind, consisting of a pound or two of white lead and this youthful indiscretion terminated in his death.”

After that he got another raven:

“The first act of this Sage, was, to administer to the effects of his predecessor, by disinterring all the cheese and halfpence he had buried in the garden – a work of immense labour and research, to which he devoted all the energies of his mind. When he had achieved his task, he applied himself to the acquisition of stable language, in which he soon became such an adept that he would perch outside my window and drive imaginary horses with great skill all day.”

There’s more:

“He new-pointed the greater part of the garden wall by digging out the mortar, broke countless squares of glass by scraping away the putty all the way round the frames and tore up and swallowed, in splinters, the greater part of a wooden staircase of six steps and a landing – but after some three years he too was taken ill and died before the kitchen fire. He kept his eye to the last upon the meat as it roasted, and suddenly turned over on his back with a sepulchral cry of “Cuckoo!” Since then I have been ravenless.”

Irish Wasps

Although all wasps seem to look alike there are actually 6 species of social wasp in Ireland. First the Vespulae – these are the ones that cause most nuisance and particularly the first two blaggards:

- Vespula vulgaris (Common Wasp);

- V.germanica (German or European Wasp);

- V.rufa (Red Wasp);

- V. austriaca (Cuckoo Wasp). V.austriaca is known as the Cuckoo wasp because it is an obligate parasite of V.rufa!

Then there are the ‘long cheeked’ wasps – Dolichovespulae:

- Dolichovespula sylvestris (Tree wasp)

- D. norvegica (Norwegian wasp)

The most numerous are the Common and German wasps and they are very similar to look at. To decide which is which you have to look them in the eye and examine their facial features. The Common wasp has an anchor shaped black patch on the front of its face while the German has an arrangement of 3 dots. Also, the black bands are wider on the Common wasp. Great photo’s here.

Both species mostly build nests underground however they will go into roof spaces but this habit is more often seen in the Common wasp. During the course of the year they will rear between 6,500 and 10,000 workers, 1,000 queens and 1,000 males. Towards the end of the summer the old queen starts to lose her power and she goes off lay. This presents the army of workers with a problems – they have spent the summer gathering insects, chewing them up and feeding them to the larvae. In return the larvae would secrete a sugary syrup which the workers take as food. When the larvae run out the workers have to find another source of sugar and end up throwing their weight about in beer gardens and kitchens. And of course creating problems for the bees.

The other two Vespulae species are less of a problem for humans or bees because their life cycles are different to those above. The Red wasp has a similar anchor shaped black patch on its face but is easily distinguished from the others by the reddish band on the upper abdomen. It builds a much smaller nest and seldom in an urban setting. It is also very much less aggressive and is (apparently) reluctant to sting.

It is parasitised by the Cuckoo wasp, the queen of which moves into the nest as soon as the first workers are up and running. She kills the Red queen and forces the workers to look after her brood which she sets about laying in the cells built for the eggs of her predecessor. They rear only males and new queens – because they use the Red wasp workers as slaves and do not need their own workers. Isn’t that awful?

The other two also build much smaller nests and although the Tree wasp can be very aggressive they seldom cause problems like the first two. The Tree wasp tends to suspend its relatively small nest from trees and shrubs but it will also nest in relatively small cavities. The Norwegian wasp also builds a small nest in trees or shrubs often quite close to the ground.

The colonies of all of the above species break up at the end of summer and only the new queens overwinter by hibernation. It’s surprising how often wasp queens can be found hibernating inside the hive roofs. In spring they wake up and begin to build their nests. They lay their eggs and they feed the brood themselves until eventually they have workers on the wing after which, the queen lays eggs exclusively and the workers tend the brood. The workers are all female and they all sting – the sting is an adapted ovipositor. The males, which emerge later in the year have no sting. Learn the difference and impress your friends. The very large wasps to be seen on the Cotoneasters early in the year are the queens.

Copyright © Beespoke.info, 2014. All Rights Reserved.

Wax-moth Hell

This is the time of year for scraping down the stack of equipment that got thrown into the shed during the active season – I know this because that’s what I’ve been doing this afternoon. Once started I realise why it takes so long to get down to it because it really isn’t nice. Not nice at all.

There should be a course -‘Entomology for Beekeepers’ because the assortment of creepy crawlies to be found in the detritus at the bottom of a beehive is bewildering and horrifying – like Doctor Who with maggots. Continue reading Wax-moth Hell