When beekeepers think heather, they think weather and ‘Will it ever stop bloody raining?’

Or you might wonder – ‘IS there a flow at all?’ Because often there isn’t and you can never tell in advance if it will or if it won’t. Heather honey is the most bewitching and frustrating of all honeys; if you can get a crop of sections or cut comb honey it’s close to heaven and so costly and disappointing when it fails.

But there’s more to it than the weather. It’s the ecology – Stupid!

Distribution

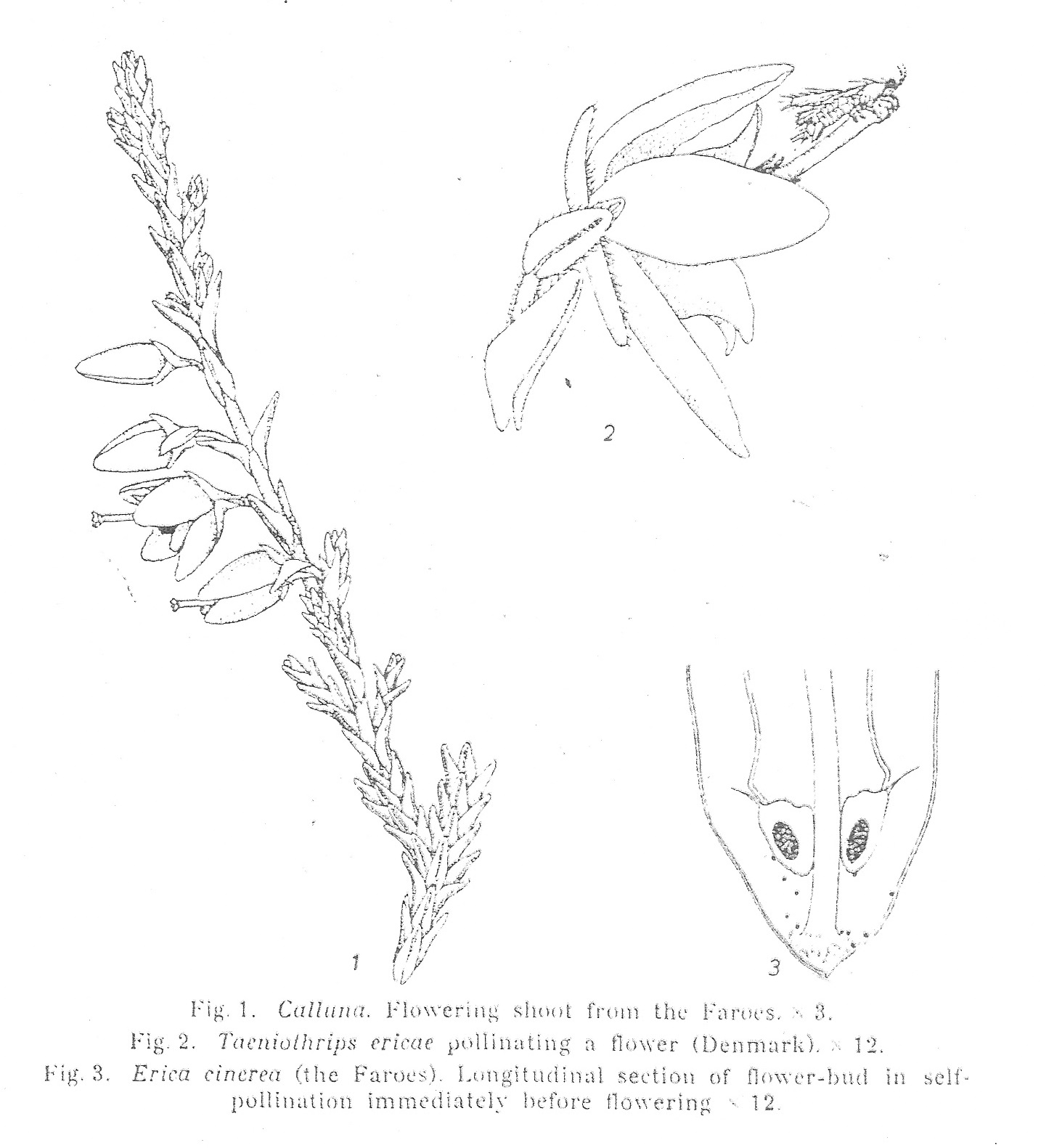

Calluna vulgaris or Ling heather is widespread at all altitudes across Northern Europe from Spain to Scandinavia and from the Azores to the Urals but tends to dominate where the environment is harsh and/or nutrient stressed. As we all know, it tolerates extreme cold without damage but it is intolerant of shade.

Soil

Calluna is seldom found in fertile lowland situations because it is a ‘calcifuge’ ie it can’t bear limey or base soils but likes instead, an acid soil. This tends to make it a plant of stressed environments, either mountain or bog where excessive rain and cold create acid soils which are also usually low in available nitrogen.

It can get a foothold in moderately receptive soil environments. Once established, the cast-off leaves decay to a dark brown acidic humus. In this way Calluna is able to adapt certain soil environments to suit its own requirements.

Moisture

While Calluna is almost always found in areas of high rainfall – it is actually intolerant of waterlogging and grows best where there is moderate drainage. In super-saturated areas Calluna tends to give way to Ericaceous heathers ie Erica tetralix or E. caerulea – also Molinea caerulea or Purple Moor Grass. Where Calluna is found growing in bogs, the roots tend to be restricted to the top few inches of peat and above the upper extent of the summer water table. If this is still too wet – it will pull up its skirts and occupy the hummocks.

Growth Habit

When it finds conditions it likes – C. vulgaris is a long lived, woody dwarf shrub – often reaching 30 and even 35 years old. The life cycle is divided into four phases:

- Pioneer – 3-6 years – flowering after the 1st year;

- Building – Up to 15 or 20 years. Densely branched shrub with maximum canopy cover and nothing growing beneath. Flowering freely;

- Mature – Over 20 years. Plants become leggy – up to 1.2 metres – with mosses and lichens beginning to occupy the open area at the centre of the plant;

- Degenerate – Over 25 years. Central branches die out leaving a gap which may be colonised by other species perhaps upland trees such as Rowan or Scots Pine before young Calluna plants can establish.

For the beekeeper, the Building and Mature phases are most useful to the beekeeper as they can give rise to vast areas of carpet-form heather which is when flowering is most profuse.

Careful burning of heather at intervals in concert with managed grazing can remove stands of degenerate heather and create instead a shifting mosaic of different aged stands of heather which are of great benefit to wildlife – especially Red Grouse (Lagopus lagopus), many species of bees and other insects. Beneficial to Hill farmers also.

Burning correctly is a skill. Ideally the fire should only kill over-mature specimens leaving younger plants to regenerate from the base and creating space to allow seeds to germinate. A slow moving fire over dry peat can get too hot, killing all heather plants and destroying the seeds present in the seed bank. In such cases regeneration is slow, if at all, and other species may move in instead. And there may be soil erosion.

Grazing

Calluna benefits from moderate browsing which can promote the aforementioned dense, single-species, topiaried carpet.

Sheep and Deer are browsers rather than grazers such as cattle: they pick and choose – mostly young shoots which is like light pruning and beneficial in its effects. However, overstocking of sheep/deer forces them to browse more deeply, and damagingly, into the woody heart of the plant. It also reduces the ability of heather to regenerate; young plants are unable to establish or are grazed to extinction leading to thinning stands of gangly, senescent heather. Excessive trampling creates bare patches leading to soil erosion or invasion of other less valuable species.

Cattle are disastrous for heather – they graze indiscriminately and their great heavy feet cause severe damage to soft peaty soils leading inevitable to soil erosion.

Heather also provides habitat for the Red Grouse (Lagopus lagopus) which relies on heather for 90% of it’s adult diet. It also requires heather of varying ages for shelter and cover and areas in which to nest and to rear young. The young birds are reared on insects foraged in the heather – the only carnivorous phase in the bird’s life. As such it is completely dependent on heather for its life-cycle.

I never heard of overgrazing by grouse – instead this bird can be regarded as the ‘canary’ when recognising when conservation is necessary. In other words – if it is absent or dwindling from heathery uplands something is wrong. Click here for the Irish Red Grouse Association.

Heather Beetle is a wild creature whose boom-and-bust life cycle can lead to overgrazing by the larvae and even death of great swathes of heather. Sometimes the whole system is replaced by other less desirable vegetation communities such as Molinia caerulea aka Purple Moor Grass with or without assorted sedges and moss. This creature, the heather beetle is also known as Lochmaea suturalis. Here it is:

In a ‘normal’ year, heather beetle harmlessly carries out its life cycle eating heather leaves and hibernating in the soil. However in some years the population rockets and the heather suffers a beetle-grazing epidemic to the extent that extensive areas are wiped out.

Here’s a picture of severe heather beetle damage in a lowland raised bog, Narraghmore, Co.Kildare:

Pollination

The flowers of Calluna are able to both self and cross pollinate but an outside agent either the wind or an insect is required in both cases. In experiments where flowers are enclosed and outside agents excluded, pollination does not occur.

If you look closely at the flowers of C. vulgaris you will see that the arrangement of pollination paraphernalia lends itself to a generalist approach enabling both insect and wind transfer of pollen.

Either way, once a flower is pollinated by the wind or another insect rather than one of your honey bees, the secretion of nectar dries up!

Wind Pollination The pollen-bearing anthers are safely enclosed within the heather flower. When weather is damp and wet, the pollen remains clumped on the anthers and is not washed away by the rain. When weather is dry and windy, however, it is liberally shaken out and blown hither and yon. The stigmas meanwhile are out in the elements where they can obviously take advantage of passing clouds of pollen. So if there is a long period of dry windy weather and the flowers are quickly wind pollinated the likelihood of a strong nectar flow is reduced.

Here’s a picture of my dog Bunty in the heather. She used to love a trip to the hills but the poor girl was the victim of a pollen allergy and the free release of heather pollen on a sunny day would set up such an itch she would spend most of her time rolling around and scratching till she bled.

Insect Pollination We are all familiar with the buzz of activity in the flowering heather what with bumble bees, honey bees, butterflies and others. Flowers are visited by about 35 species of insects.

Nectar to attract insects is secreted from nectaries inside and at the base of the flower below the anthers. As such, visiting insects inevitably transfer pollen from their bodies onto the stigma and pick up pollen from the anthers as the reach down for the nectar.

Bumble bees and honey bees are the most efficient pollinators as they carry the most pollen and they get up very early in the morning!

Thrip pollination The architecture of heather flowers does not allow for rain pollination. However where Calluna lives it can rain for days or even weeks on end. No surprise then, that heather does have a trick up its sleeve for those wet years when neither wind nor flying insects can do the job.

There is a tiny creature – a thrip – called Taeniothrips ericae – which is found on both Calluna and Ericaceous heathers. It spends almost its entire life cycle within the flowers, romping about between the anthers picking up pollen and eating nectar. There are about 4-6 thrips per flower but male thrips are rare. As a consequence females leave home on sexual maturity and roam from flower to flower looking for a mate. The picture below from Hagerup (1950) shows a female thrip using the stigma of a flower as a launch pad (Figure 2.). No doubt she lands on many of these during her wanderings and inevitably pollination must occur. Later work in Norway by Haslerud (1974) concluded that pollination by thrips was only significant in very wet climates. Click picture for a close up.

By the way, pollination aside, these insects have the same boom and bust life cycles as the heather beetle and Irish developers. In boom years each flower may be full of baby thriplets eating all that heather nectar before our bees can get there. And you know yourself how the honey bee hates competition – they’ll just go for the ivy instead!

In Essex I remember plagues of tiny black corn thrips or ‘Thunderbugs’; some years the air would be full of them. They’re probably extinct now.

A Hardy Plant?

In the absence of over-grazing by mammals, birds or insects – Calluna fares surprisingly well in hostile environments on acid/nutrient poor soils and in cold, wet, upland areas with strong winds etc. It grows quickly into a large, long lived, vigorous plant which puts out a profusion of flowers year on year.

How does it do it?

Read on…

Mycorrhizal Symbiosis

To cope with the stresses of the very extreme environments of mountain and bog, Calluna has evolved a symbiotic relationship, with an assortment of soil fungi including Rhizocyphus ericae and Phialocephala fortinii complex. Fungi involved in these symbioses are termed Mycorrhizae or ‘fungus roots’.

Don’t go away – this is simpler and far more interesting than you can imagine!

Here is the simplified basis for Calluna’s mycorrhizal symbiosis:

- Calluna is nitrogen-limited because there is so little available in the stressed environments it inhabits but it does have an unlimited supply of carbon which it captures from the air via photosynthesis.

- Fungi, on the other hand, are enzymatic powerhouses – well able to break down acidic litter and suck up nitrogen in conditions which thwart most plants. As a result, soil fungi have an abundance of nitrogen but they are carbon-limited.

The roots of the heather link up with microscopic fungal hyphae thus plugging themselves into a fungal network of mycellium which ramifies outwards through the soil breaking down litter and supplying nitrogen to the plant which in return supplies carbon products to the fungus.

There’s more – these fungi are termed endomycorrhyzas which means they actually penetrate the roots and grow inside the plant as well – a hand in glove relationship! Fungal hyphae can be found throughout the plant even as far as the ovules with their ripening seeds. Sounds a bit like The Borg (1992,1996) don’t it? Researchers believe that in this way, plants are inoculated with their mycorrhyzal partners when they are seeds – how clever is that!

Conservation

A survey of potential Red Grouse habitat in Ireland in 2008 revealed 22% of the total grouse habitat to be severely damaged by overgrazing, 30% moderately damaged while only 34% remains undamaged. For Red Grouse Habitat read Calluna vulgaris.

It should be of concern to beekeepers as well as sheep farmers that over 50% of total heather is damaged.

Sources

Crushell,P. & O’Callaghan, R.J. (2008) A Survey of Red Grouse (Lagopus lagopus) Habitat in Ireland 2007 – 2008: an assessment of habitat condition and land-use impacts. Report for BirdWatch Ireland & The National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government, Ireland.

Gimmingham,C.H. (1960) Biological Flora of the British Isles: Calluna vulgaris Journal of Ecology

Hagerup, O. (1950). Thrips Pollination in Calluna. K. Danske vidensk. Selsk., Biol. Medd., 18 1-16

Hazard.C., Gosling.P., Mitchell.D.T., Doohan.F.M. & Bending.G.D. (2013) Diversity of fungi associated with hair roots of Ericaceous plants is affected by land use. Article first published online: 28 NOV 2013. DOI: 10.1111/1574-6941.12247. © 2013 Federation of European Microbiological Societies

Haslerud, H.D. (1974) Pollination of some Ericaceae in Norway.

Nord. J. Bot. 21: 211–216.

Mahy, G., De Sloover, J., & Jacquemart,A. (1998) The generalist pollination system and reproductive success of Calluna vulgaris

in the Upper Ardenne. Can. J. Bot. Vol. 76 1843-51

Mohamed, B.F. & Gimmingham,C.H. (1970) The Morphology of Vegetative Regeneration of Calluna vulgaris. New Phytologist. 69, 743-750

Rayner,M.C. (1925) The Nutrition of Mycorrhiza Plants : Calluna vulgaris. Journal of Experimental Biology

Star Trek: The Next Generation: I Borg Season 5, Episode 23 (1992)

Star Trek: First Contact (1996)

Copyright © Beespoke.info, 2015. All Rights Reserved.