Once upon a time, all beekeepers would have made their own skeps using materials they could find locally. The theory of skep-making is simple enough: a length of straw rope, tapered at each end is coiled into a basket shape and stitched into place with a tough binding. It is a time-consuming and messy business though and should be done either outside in the elements of a warm, breeze-free day or in the corner of a garage or workshop. I should add that it takes practice.

Materials

There are two categories of materials:

- the coil of rope forming the body;

- the binding holding it in place.

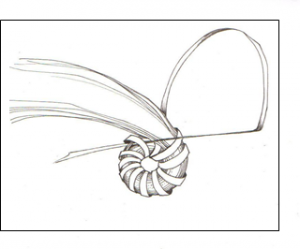

A variety of different materials can be used for each, depending on what is readily available – selection below. Click image for close up.

The Rope

The rope can be straw, grass, rush and even heather – almost anything fibrous which is relatively long, tough and flexible can be used. Some materials are more durable than others and generally, the tougher the material the more difficult it will be to work.

Oat straw makes a good lightweight skep and was the most commonly used material in this far flung corner. Wheat or barley straw will also suffice you just need to find some with nice long stems.

Rushes such as the common soft rush Juncus effusus are soft and easy to work with but the central pith will take up atmospheric moisture and the skep will soon rot.

Purple moor grass, Molinia caerulea, is an exceptionally tough and durable upland grass found throughout Britain and Ireland and used for skep making in Scotland. There’s a lot of that around here so that’s what I started with. You can use either the leaves or the flowering stems and the plant obligingly sheds both in the autumn so you can go along and just pull it up by the handful. The leaves are nice and soft and easy to work but the flowering stems tend to be a bit brittle. They are easier worked if they are a little green when gathered but once dried no amount of soaking will de-brittle them enough to make them turn tight corners but they can be incorporated into the skep walls.

Click here for more on Purple Moor Grass

The Binding

Whatever the chosen material for the rope, the binding would traditionally have been bramble or sometimes nettles.

Brambles aka blackberry or Rubus fruticosus were were traditionally used, probably because they grow almost everywhere and they are so tough but the preparation is labour-intensive: the fronds should be one year old growth and no older as the stems become woody and tough with age; these need to be cut in the late summer or early autumn and stripped of leaves and thorns before being split lengthways, de-pithed and stropped to improve their pliancy. Finally they can be hung somewhere cool and dry to season.

Nettles have their own problems.

There are modern alternatives. Jute or other hairy strings are convenient and cheap but their durability is variable and some sources suggest that the hairiness and the smell of oils used in their manufacture are irritating to the bees. Synthetic baling twine is the cheapest of all and can be used if you don’t mind blue (or orange) but it will degrade in sunlight and your skep may burst asunder at a vital moment.

Lapping or binding cane is a renewable rattan product from the Far East and is a reasonably priced alternative, there is little preparation and it comes in the post. If lapping cane is used, ideally it should be pre-soaked for several hours to increase its pliancy.

Tools

- A bodkin or marlin spike to pierce the rope;

- A section of cow horn or the neck of a plastic bottle to hold and funnel the material into a continuous rope of uniform thickness;

- Scissors;

- Tape measure;

- Long nosed pliers.

Method

The skep is begun from the centre with the inside of the basket towards you. Work progresses outwards in a flat spiral then gradually the coils are directed upwards to make the walls, finally tapering off at the rim.

The first and most difficult thing to do is to get started.

- First take a soaked length of lapping cane and form a simple knot and – holding it this way up with the long end to the left…

- Take 3 straws and, working with the thin ends lay them across the active length of cane (the one on the left) then bring the cane over and pass it through the loop trapping the straws thus;

- You need to stop now and think because the direction in which you start the binding is very important – once begun it cannot be changed. If you are right-handed you will probably load material into your rope from the left, leaving your right hand to do the stitching. The inside of the skep is facing you;

- Continue binding the straws to the centre by passing the cane though the centre each time and slightly overlapping the previous stitch until you have completed a full circuit and it should look someting like this from the inside…

And like this from the outside… an eyelet with the smallest possible hole in the middle.

And like this from the outside… an eyelet with the smallest possible hole in the middle.

- You can now start catching the stitches of the previous coil and as you do so, you need to start adding straws – this time add them one at a time butt end first – push them into the middle of the others until they grip.

- With the scissors, trim the working end of the cane to a point and use the bodkin to ease a passage beneath a stitch then push the cane through. Pull tight and repeat, binding the coils to one another as they expand.

- Loading the rope is important. Keep loading one or two straws at a time, gradually building it up until it is thick enough to fit the horn or plastic guide. From then on it is important to maintain a snug fit in the guide by loading little and often. Do not allow the guide to become slack as this will introduce a weakness. Too tight and you’ll get a bulge.

- Give the rope a twist as you go and this will further tighten the structure;

- As you progress away from the centre, the stitches will become further apart so you should add stitches periodically by tightly circling the rope once with the lapping cane between stitches and holding it tight until the next stitch locks it into place. If you are making your own skep the size is completely up to you but generally a swarm skep has an outer diameter of about 14” and height of 10” and will take about a day to make. Harking back to grain measures – a 15”x10” skep holds one peck, or a quarter bushel, while one of 14”x15” will hold about 2 pecks – half a bushel. Which size you choose depends on your average swarm size – 1 peck or 2!

- Start the walls about 2” before you have reached the required base diameter because it will take a couple of laps to round the shoulder fully. Up until now you have been binding coils one to another in a flat disc but now you need to change the both alignment of the coils, one upon the other, and the positioning of the stitches. Remember you have the inside of the skep towards you.

- Finishing off is just a matter of finding the right place to stop so there isn’t a lop-sided look. Once that is decided, stop loading the rope but continue the stitching until the rope tapers off to a point then just tie off the end and thrust it out of sight.

Click here for 2019 Skep Course

Click here for guidance on how to add a new binding cane

Click here for more on Purple Moor Grass

Click here for Skeps and Skep Beekeeping

Copyright © Beespoke.info, 2015. All Rights Reserved.