So, why are honey bees such important pollinators?

From an ecological point of view there are at least 3 reasons:

- Honeybees have evolved in tandem with certain flowers and they have adapted to facilitate each other;

- One bee is able to rapidly communicate the location of a pollen/nectar source to the whole hive and an army sets out;

- The bees then concentrate faithfully on that flower species until the pollen runs out or the nectar dries up, at which point the job of pollination is accomplished.

These features obviously make the honey bee important from an agricultural/commercial point of view. In addition, hives of bees are mobile and can be moved from crop to crop – an arrangement which can suit bees, farmers and beekeepers so long as everyone has a bit of respect. Wouldn’t that be great?

But some detail:

Evolution

In the beginning there was the wind…

The earliest seed-bearing plants were randomly pollinated by wind-borne pollen which would be caught on droplets of a sticky exudation oozing from their ovules. Because of the hit and miss nature of this method of pollination massive amounts of pollen need to be produced in the hope that at least some of it will find its mark. This method is still used by conifers.

Then came the insects…

It is thought that eventually sap-sucking or resin-browsing insects were drawn to dine on the exudation. The effects of this were beneficial to both parties – the insects were introduced to pollen as a new source of protein and as they moved around from plant to plant they carried pollen with them and pollinated as they went. Plants pollinated in this way needed to produce less pollen than those still relying on the wind. Insect pollination was also more efficient so these plants were able to produce more offspring and the trait persisted.

Co-evolution

As long as such associations are mutually beneficial, their continuance is at least assured and there may even be further co-evolution. Each step along the co-evolutionary pathway creates a more fruitful relationship although things are more prone to disaster.

Over-dependency

Occasionally a plant may devise an almost perfect method of manipulating an insect for pollination purposes but such cases are so complex they tend to involve a single species of insect. One of the best examples of this is the flower of the orchid Ophrys speculum which looks enough like the female of a certain bee species (not Apis mellifera) to entice pollen coated male bees to mate with it and thus pollinate it in a novel way. While this may be a highly successful method of pollination, the future of the orchid becomes tied in very closely to that of the bee; if the bee species should decline or even become extinct, perhaps due to habitat destruction or a surfeit of exhausted males, then the orchid will be doomed to follow.

Honey bee adaptations

The honey bee has not yet been so tightly hemmed in by co-evolution and they remain relatively broad spectrum pollinators. However they have evolved certain adaptations that suit them for their job such as tube-like mouthparts for reaching down into the throats of flowers in search of nectar and the hairy body which is the ideal surface to which pollen grains will easily cling. There are also pollen baskets but these are designed not for the passing on of pollen but to collect the bee’s share to take home to the hive.

Bee flower adaptations

Plants, for their part, have adapted their flowers to attract bees – all sorts of bees. They tend to have brightly coloured petals, usually blue or yellow, with a landing platform of some sort. The petal markings may include honey guides which are designed to tell the bee where the nectar is. The nectaries are tucked away near the base of the corolla tube, where only the tube-like mouth-parts of a bee can reach and inaccessible to the chewing of beetles.

There are also cunning floral booby traps designed to manipulate the insect pollinators:

- Scotch broom – Cytisus scoparius is spring-loaded to burst open when a bee lands, the curved stamens and stigma arching over the bee; the stamens to press pollen onto its back and the stigma hoping to pick up some suitable pollen placed there by another broom plant.

- Gorse (Ulex europaeus) is also spring loaded but in this case the stigma and stamens burst from the floor of the flower, hoisting the bee into the air. Here the target must be the bee’s belly.

- Rosemary officinalis is not sprung, but has stamen and stigma strategically arranged to arch out of the upper part of the flower in such a way as to brush the bee’s back.

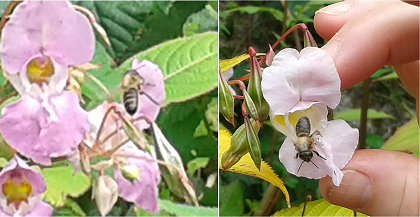

- Himalayan balsam or Impatiens glandulifera has stamens situated above the entrance of the flower so as the bee pushes its way in – a streak of white pollen is plastered onto its thorax

- Meadow sage or Salvia pratensis has a carefully placed foot-plate which is hinged to the stamens, when the bee treads on the foot-plate the stamens swing down from the roof of the flower stamping pollen onto its back. The stigma, meanwhile, extends from the upper lobe of the flower and lengthens with age so that bees entering an older flower brush against it on the way in so delivering the pollen. Presumably this age-related lengthening is a mechanism to avoid self pollination. Click this fabulous photo below for a close up of Salvia pratensis pollination in action – not mine and not a honey bee – all credits to Wikimedia.org

So a day in the life of a honeybee can be quite a circus, hoisted into the air one minute and thumped on the back the next.

Honey bee exclusion

Some flowers have evolved to exclude honeybees in favour of other insects.

A common method of exclusion is by having corolla tubes too deep for the bees’ elongated mouthparts and these are butterfly flowers. An example would be honeysuckle (Lonicera periclymenum). Unimaginative though – don’t you think? How about weight activated trapdoors, ejector seats or that old favourite – a boxing glove on a spring.

However, exclusion can backfire. Some insects are clever enough to chew a hole into the corolla tube to access the nectaries bypassing the pollination step altogether. Honey bees will sometimes use these access holes too.

Another exclusion method is an open door policy. Primitive flowers such as composites (daisy-like flowers) are open to all and sundry. These are little visited by honeybees as they are not mixers by nature and dislike competition.

Wild carrot (Daucus carota) flowers are white composites but they sometimes have one small red flower in the centre (above).This is thought to attract flies who think the little red dot is another fly and flies are great mixers. Just look at horse muck!

Communication

The foraging force of any one hive may number 25 thousand and they will cover the area within a radius of 3 miles from the hive in search of nectar and pollen. When they find a good source, they become very purposeful, they load up with pollen and/or nectar, then they go back home to the hive. Once home they will hand out samples of what they have found and dance enthusiastically to tell everyone where it came from – how far, how much and which direction. Bees that respond to the dance and go out and find the source are said to be ‘recruited’. For bees, this means they will go out after this species of flower until either they die or the source does. Communication means that a chance discovery by one bee will lead to thousands and thousands following on and obviously the more bees the quicker will be the pollination.

Good Youtube video on dancing bees here:

Fidelity

The fidelity bees show for a single species helps pollination in several different ways.

- Once they have been discovered by the bees, increasing numbers of bees are recruited to forage on that species moving from flower to flower depositing pollen as they go.

- They will continue to visit until either the nectar dries up or the weather changes. They make the most of spells of good weather.

- When the bees return to the hive they all tumble around together in the hive, passing pollen from bee to bee as they brush shoulders. This increases the likelihood of cross pollination as bees will then be carrying pollen from several individuals of the same species.

- Focussed attention means plants need not produce so much pollen.

Mobility

From a commercial/agricultural point of view, hives of bees can easily be moved from crop to crop where all of the above apply. Bees are regularly employed to pollinate crops of oil seed rape, borage (star flower) and top fruit in the UK.

Meanwhile in the USA, fruit farmers and beekeepers have evolved a highly efficient annual migratory existence following a variety of crops west to east by the truckload across the country. They are paid for their services as pollinators and of course there is the honey too. Crops they are paid to pollinate include apples and pears, cherries and almonds, melons, cucumbers and squash, cranberries and sunflowers. For honey there are orange blossom, alfalfa, California buckwheat, blueberries, Brazilian pepper, palmetto, basswood, clover and gallberry to choose from.

It could be said that they have, between them, created a specialist relationship like the delicate orchid/bee example above. One that is very focussed and even efficient but also very vulnerable and we’ve seen what can happen with the disastrous Colony Collapse Disorder.

Here in Ireland, while farmers will welcome beekeepers onto their land when they are growing oilseed rape or apples etc there are few who will pay the beekeeper to move.

But read on…

The Future

The drive towards increasingly intensive agriculture is accelerating. Each year, more hedgerows and patches of scrub are ruthlessly wiped off the landscape and mixed meadows reseeded with rye grass. Habitat destruction causes the extinction of wild pollinators and this may lead to an increase in demand for mobile beekeepers here but we should know where that stuff leads.

But always look on the bright side of life – that’s my motto!

Click here for the mechanics of Pollination

Click here for more on Gorse Pollination

Click here for more about Himalayan Balsam

Click here for Ireland’s Pollinator Plan 2015-2020

Sources

Attenborough,D. Life on Earth – A Natural History. BBC, William Collins and Reader’s Digest. 1979.

Campbell,N.A. Biology – Second Edition. The Benjamin Cummings Publishing Company Inc. USA. 1990.

Mairson,A. America’s Beekeepers – Hives for Hire. In National Geographic Vol. 183 No. 5. 1993.

Raven,P.H., Evert,R.F. & Eichhorn,S.E. Biology of Plants. Worth Publishers Inc., New York. USA. 1986.

Copyright © Beespoke.info, 2016. All Rights Reserved.

Thank you very much for your most-detailed and informative website. However, your site does not address something that I discovered at The Basin, Victoria a few days ago. I was trying to capture a good close-up photograph of a honeybee approaching a flower. My first attempt was unsatisfactory, but my second picture appears to have captured something I have never heard of: the bee is clearly clutching a flower stamen. No, it is not just the bee’s long hind legs, and I would appreciate your comments. Your site does not support uploads, but please feel free to email me if you would like a copy of my bee and her unusual payload.