The sting of bees and other Hymenopteran insects is thought to be a modified ovipositor. An ovipositor is a pointed tube used to pierce a hole to lay an egg into. Honey bees have evolved beyond the need for an ovipositor – instead they have adapted it as a weapon and despite the fact that using their sting is accompanied by disembowelment – they are not afraid to use it.

Housing

When not in action it is housed out of sight in a little pocket within the sting chamber at the rear-end of the abdomen where its hangs suspended from the sting chamber membrane.

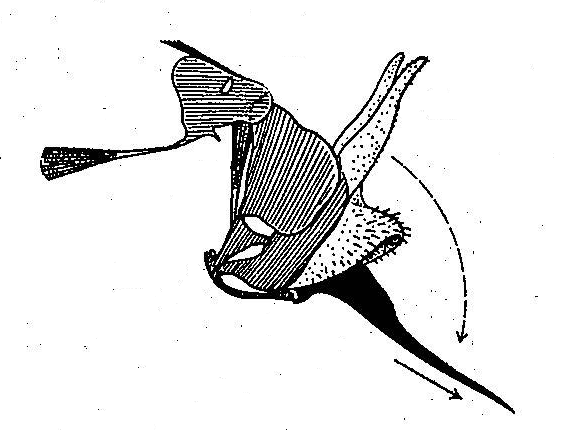

In repose the stinging apparatus is pulled in and tucked away rather like the back-actor of a JCB in transit (the shaft of the sting corresponding to the bucket); folded in such a way that the business end, the sting itself, is safely scabbarded within a two-lobed sheath. The two lobes of the sheath are to the right of this picture and the tip of the wicked black sting is just visible beneath.

Stinging Apparatus

- The shaft of the sting is made up of three long, slender, pointed, pieces – the stylet and 2 barbed lancets. These all slot together, the two lancets side-by-side with the broader stylet on top, in such a way that all three parts are able to slide freely and independently. A channel runs between the three pieces and it is through this that the poison is dispatched;

- The venom gland which makes the poison, feeding it into a venom sac, where it is stored until needed;

- The alkali gland which supplies a lubricant to the base of the shaft, presumably to assist its penetration into the skin of the victim.

Stinging Mechanism

When called into action the apparatus drops down releasing the shaft from the sheath allowing the sting to swing into the ‘ready’ position – poised with the point protruding from the tip of the abdomen thus:

When the worker bee stings, the abdomen is thrust sharply downwards, pushing the shaft of the sting into the skin of the victim where the lancet barbs give it its initial hold. As if that wasn’t enough the lancets are then alternately forced deeper and deeper in, the barbs holding each successive gain and the interlocked stylet charging in from behind sliding down the lancets and further into the wound made by them. Valves on the base of the lancets drive venom down the poison channel where it is released into the wound.

Bloody Hell!

The interaction of a series of cunningly placed muscles and hinged plates continues to push and pull the sting deeper and deeper into the unfortunate victim even after the stinging apparatus has become detached from the bee. When the sting is detached from the bee, the guts follow and the bee dies.

A couple of photos here – click for a close up of my pain.

When removing a sting – scrape it from the wound outwards rather than trying seize it by that handy looking little bulb on the end because that’s the venom sac and squeezing it will empty the remaining venom into the wound.

Sources

Hooper,T. Guide to Bees and Honey. Blandford, London. 1991.

Snodgrass,R.E. The Anatomy of the Honey Bee. In The Hive and the Honey Bee. Ed. Dadant and Sons. Dadant Publications. Illinois. USA. 1979.

Copyright © Beespoke.info, 2016. All Rights Reserved.