Willows (Salix spp.) bloom early in the year – February or March – and are very important and popular with the bees which can be seen thudding onto the landing board bearing very large loads of powder-yellow pollen. In an exceptionally warm spring the bees may even bring in a small crop of honey but this is very rare.

They are a complex group of many species ranging from ground hugging mountain shrubs, to graceful riverside trees. Despite their diversity of form and habitat, willows are often to be found in wet, boggy places or close to water.

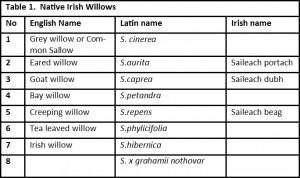

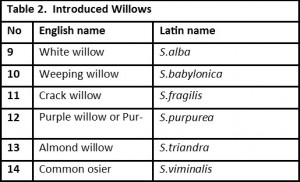

Of the twenty or so species present In ‘These Islands’, fourteen are thought to be present in Ireland (see Tables 1 and 2) although only eight of these are considered native (Table 1). The tea leaved willow (6) is on the Irish Red List: a list of species in danger of extinction in Ireland.

Two further willows (7&8) are found only in Ireland but these too are very rare:

- Irish willow – a shrubby species known only on Ben Bulben in Sligo;

- a hybrid known only from Muckish Mountain, Donegal and so rare it only has a Latin name!

Both are on the International Red List: a list of species in danger of extinction internationally.

All willows readily interbreed so in addition to the true species there are lots of confusing hybrid intermediates.

For the bees

Most willows are dioecious – that is individual trees are either male or female. Catkins appear on separate trees from March to May depending on the species. The catkins are grey and silky at first – when they are known as pussy willows. When fully open, the males become quite showy due to the copious amounts of clearly visible yellow pollen – see below.

While the females are more subdued in appearance – greenish and inconspicuous – see below.

Willows are thought to be predominantly wind pollinated but in favourable conditions the flowers of both sexes will produce nectar to attract insects including bees.

Commercial osier growers propagate varieties by taking cuttings, which root easily, to ensure pure strains and the right sex. To ensure early forage for their bees, beekeepers can easily follow suit and take winter cuttings of early flowering varieties to push into local hedgerows. Cuttings should be about a foot long and the thickness of a stout pencil.

For man

Willow is not renowned for the quality of its timber. However, white willow wood is light-weight and strong in a fibrous, springy sort of way making it sought after in a few specialised areas such as the manufacture cricket bats and artificial limbs!

A specially bred cultivar – S.alba ‘Caerulea’ – also known as the cricket bat willow – is grown and managed along watercourses in the south east of England exclusively for the cricket bat industry.

Coppice

Willow really comes into its own as a fast growing coppice crop. There are several commercial uses of willow coppice including basketry and biofuel.

For basketry, willows (generally cultivars of S.viminalis, S.purpurea and S.triandra) are harvested every winter by cutting at ground level, which means that unfortunately they never bear flowers. All willows grown and harvested in this way are termed osiers although S.viminalis is the most common and is easily recognisable by its distinctively long, narrow leaves.

Short rotation coppice for biofuel differs in that it is cut every 3-5 years after which the wood is chipped and burnt in special wood-burning furnaces producing steam to drive turbines which in turn produce electricity. As willow grows quite well in Ireland this is a crop that could be considered for biofuel production here. Willow flowers are borne on the previous season’s growth so biofuel willow coppice should be of use to bees.

Pollard

Pollarding is a practice that has all but died out at this end of Europe (although the French remain masters of the art) but it could come back as a source of biofuel. It is similar to coppice in that it too involves the regular cutting of a tree, usually white willow or crack willow, but in this case it is young trees, which are cut at a height of 2m. The docked stems then throw out dozens of side shoots – at 2m this is above the height of browsing cattle. The shoots are allowed to grow for several years depending on the intended use i.e. firewood, small stakes for general use such as fencing or wands for weaving hurdles or rough baskets. A side benefit to the cultivation of white willow and crack willow, (pollarded or not) as riverside trees is that they have knotted and extensive root systems, which help to stabilise the banks and prevent erosion by flood-waters.

Click here for Bee Trees – Hawthorn

Click here for Bee Trees – Hazel

Click here for Bee Trees – Horse Chestnut

Click here for Bee Trees – Poplar

Click here for Bee Trees – Sycamore

Copyright © Beespoke.info, 2014. All Rights Reserved.

Sources

Clapham,A.R., Tutin,T.G. & Warburg,E.F. Excursion Flora of the British Isles. Third Edition. Cambridge University Press. 1981

Edlin,H.L. The Tree Key. Frederick Warne, London. 1978

Hooper,T. Guide to Bees and Honey. Blandford, London.1971

Howes,F.N. Plants and Beekeeping. Faber and Faber, London 1945

KebleMartin,W. The New Concise British Flora. Rainbird, London 1963

MacCoitir, N. Irish Trees Myths, Legends & Folklore. Collins Press, Cork. 2003